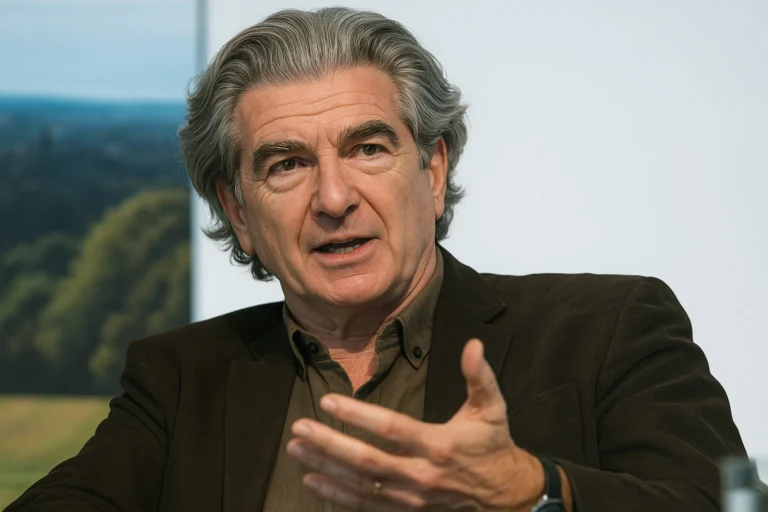

Dan Hodges: The Unconventional Voice Redefining British Political Commentary

In the cacophonous arena of British political punditry, where voices often blend into a predictable chorus, Dan Hodges stands apart. He is not a creature of Westminster’s smug inner sanctums, nor a remote academic theorist. Instead, Hodges has carved a unique niche as a columnist, commentator, and author whose work is defined by a potent combination of deep Labour movement lineage, contrarian instinct, and a street-fighting rhetorical style. His journey from Labour Party insider to one of its most prominent and blistering critics is a narrative that mirrors the tumultuous transformations within the British left over the past three decades. To understand the forces shaping modern political discourse is, in part, to understand the perspectives and provocations of Dan Hodges. This article explores his career, his ideological evolution, his methodology, and the undeniable mark he has left on how politics is analyzed and argued in the public sphere.

The Formative Years and Political Inheritance

Dan Hodges was born into a political tradition. As the son of Glenda Jackson, the revered Labour MP and actress, and the grandson of traditional Labour voters, politics was less an academic subject and more the family business. This upbringing provided an intimate, ground-level view of the Labour Party’s soul, its internal battles, and its connection to the electorate long before he ever filed a column. It gifted him a visceral understanding of Labour’s emotional core, which would later make his critiques from the right of the party so personally resonant and, to some, so acutely painful.

This insider heritage was balanced by a career beginning in the pragmatic world of trade unionism and Labour Party organisation. He worked for the GMB union and within Labour’s campaign machinery, roles far removed from the rarefied air of national journalism. This dual perspective—the emotional inheritance and the operational grind—forged a commentator who distrusts pure dogma and places a premium on electoral realism. Hodges didn’t just study Labour’s successes and failures; he had a hand in them, an experience that fundamentally shapes his impatience with what he perceives as ideological self-indulgence at the expense of political power.

The Evolution from Insider to Independent Critic

Hodges’s early journalistic output was situated within the Labour fold, but the pivotal shift began around the era of Ed Miliband’s leadership and crystallised with the rise of Jeremy Corbyn. Observing what he saw as the party’s strategic drift from the electoral centre-ground and its adoption of a politics he considered unelectable, Hodges’s commentary transformed. He moved from a critical friend to a formidable adversary, using his platform at The Telegraph and later The Mail on Sunday to deliver forensic and often scathing assessments of Labour’s direction. This was not the criticism of an outsider; it was the disillusioned analysis of someone who believed the party was abandoning its historic mission to govern.

This transition defined the public persona of Dan Hodges. He became synonymous with a specific form of centre-right Labour critique, one that appealed to a segment of the electorate and commentariat feeling alienated by their own party’s trajectory. His independence was his brand. No longer bound by tribal loyalty, he positioned himself as a free agent whose sole allegiance was to a hard-nosed analysis of power, strategy, and public sentiment. This stance, while attracting accusations of betrayal from the left, cemented his reputation as a commentator willing to follow his arguments to uncomfortable conclusions, regardless of whose sensibilities were bruised.

The Hodges Methodology: Contrarianism and Electoral Realism

At the heart of Dan Hodges’s commentary is a methodology built on two pillars: a deliberate contrarianism and an unwavering focus on electoral realism. He often gravitates towards arguments that challenge the prevailing media or political consensus, not for mere shock value, but to probe weaknesses in accepted narratives. Whether questioning the durability of a polling lead or challenging the strategic wisdom of a popular policy, his work serves to stress-test the assumptions dominating the day’s news cycle. This makes his columns essential reading, even for those who consistently disagree, as they force engagement with countervailing viewpoints.

The second pillar, electoral realism, is his true north. Hodges evaluates political actions primarily through one lens: will this help win or lose elections? This utilitarian approach often brushes against more ideologically pure positions. For him, a policy is not “good” simply because it is morally just or theoretically sound; it is “good” if it persuades a sufficient number of swing voters in key constituencies. This relentless focus on the mechanics of winning can appear cynical, but it stems from his core belief that political power is the prerequisite for achieving any meaningful change. To him, a party that does not first master the art of electioneering is merely a protest movement with a fancy logo.

Key Themes and Philosophical Stances

A recurring theme in the work of Dan Hodges is the critique of what he terms the “London liberal bubble” or the “woke left.” He argues that an overly metropolitan, culturally progressive activist base has detached the Labour Party from its traditional working-class constituents in towns across the Midlands and the North. His commentary frequently centres on issues of national security, patriotism, and crime, areas where he believes Labour has ceded ground to the Conservatives at great electoral cost. This analysis was central to his explanation of the “Red Wall” collapse in the 2019 general election.

Furthermore, Hodges is a staunch Atlanticist and a robust supporter of a strong UK-US security relationship. His writing on defence and foreign policy often carries a hawkish tone, emphasising military capability and the realities of global power competition. Domestically, he advocates for a reformed, muscular centrism that reclaims the language of nationhood and order while pursuing economic social democracy. This philosophy positions him firmly in the tradition of Blairite revisionism, albeit adapted for a post-Brexit, post-Corbyn political landscape where old certainties have been upended.

The Impact on Public and Political Discourse

The influence of Dan Hodges extends beyond his column inches. Through regular television and radio appearances on platforms like BBC Question Time, Sky News, and talkRadio, he has become a familiar face and voice in British political debate. His style in these formats is direct, combative, and clear, designed to cut through studio ambiguity. He serves as a particular kind of antagonist—one who can debate left-wing guests from a position of intimate knowledge of their own playbook, making him a formidable and often frustrating opponent for progressive spokespeople.

His impact is also felt in the way he shapes arguments for a broader centre-right audience. By articulating a critique of the left from a perspective that understands its internal language and history, Dan Hodges provides a persuasive framing for viewers and readers who may feel politically homeless. He validates concerns about Labour’s direction from a standpoint that cannot be easily dismissed as ignorant or malicious Tory propaganda. In doing so, he plays a significant role in the battle of narratives that defines modern political campaigning, influencing how both supporters and detractors of the Labour leadership conceptualise their strengths and vulnerabilities.

Notable Controversies and Critical Receptions

No commentator of his profile operates without controversy, and Dan Hodges has attracted significant criticism throughout his career. From the left, he is frequently accused of being a “red Tory,” a turncoat who provides intellectual cover for Conservative governments by focusing his fire exclusively on Labour. Critics point to his columns in traditionally right-leaning newspapers as evidence of a political migration that has abandoned progressive principles in favour of a reactionary populism. His tone, often described as dismissive or scornful towards those he disagrees with, also draws accusations of bad faith and contributing to a coarsened political culture.

Conversely, from some on the right, his Labour past and occasional criticisms of Conservative policy can mark him as an unreliable ally. His commitment is seen not to a party, but to his own particular brand of ideological analysis. These controversies, however, are integral to his position. They demonstrate his stated independence; he is, by his own design, a figure who exists in the contested space between traditional political tribes, pleasing neither fully but commanding attention from both. The friction itself is a testament to the relevance of his interventions.

Sam Lovegrove: The Visionary Leader Redefining Modern Business Strategy

The Author and Broadcaster: Expanding the Repertoire

Beyond the weekly column, Dan Hodges has expanded his influence through long-form writing and broadcasting. His book, The War of the Words: How to Win the Battle for the Modern Political Narrative, delves deeper into the themes that dominate his journalism. It analyses how political language, metaphor, and storytelling shape electoral outcomes, applying his realist framework to the architecture of political communication. The book allows him to develop arguments more comprehensively than a 900-word column permits, solidifying his intellectual thesis.

In the broadcasting sphere, his contributions are defined by the same pugnacious clarity. Whether providing instant election-night analysis or dissecting a week’s political dramas on a panel show, he brings a producer’s understanding of political theatre. He knows how narratives are built and broken, and his commentary often focuses on the strategic missteps and communications failures behind the headlines. This multi-platform presence ensures that the perspectives of Dan Hodges permeate the political ecosystem, from quick social media reactions to sustained analytical arguments in print.

Comparative Analysis: Hodges and His Contemporaries

To fully situate Dan Hodges in the media landscape, it is useful to contrast his approach with that of other prominent political commentators. The table below highlights key distinctions in style, ideological anchor, and perceived audience.

| Commentator | Primary Platform | Ideological Anchor | Core Methodology | Stylistic Hallmark | Perceived Core Audience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dan Hodges | Mail on Sunday, Telegraph | Electoral Realism / Blairite Centrism | Contrarian analysis, focus on strategy & electability | Pugnacious, clear, scornful of dogma | Disaffected centrists, right-leaning Labour voters, pragmatic Conservatives |

| Owen Jones | The Guardian, Independent | Democratic Socialism / Left-populism | Ideological advocacy, grassroots movement-building | Passionate, polemical, narrative-driven | Progressive activists, the left-wing base, young voters |

| Andrew Neil | Various (Formerly BBC) | Thatcherite Conservatism / Market Liberalism | Forensic interrogation, holding power to account | Incisive, intimidating, master of detail | Politically engaged viewers, conservatives, seekers of rigorous debate |

| Megan Greenwell | (Editorial Note: Fictitious example for structure) | Liberal Technocracy | Policy-depth, institutional reform | Analytical, detailed, solutions-oriented | Policy professionals, institutionalists |

This comparison underscores Hodges’s unique selling point: he is not a pure ideologue like Jones, nor a traditional small-c conservative like Neil. He is a strategic analyst whose ideology is inextricably linked to the practical pursuit of centre-left political power. His frequent disagreements with figures like Owen Jones are not just political but philosophical, representing a fundamental clash between a politics of principle and a politics of power.

The Legacy and Enduring Influence

The legacy of Dan Hodges is still being written, but its contours are clear. He has demonstrated that there is a substantial audience for commentary that refuses to conform to simplistic left-right binaries while maintaining a coherent, consistent philosophical core. He has shown the potency of arguments grounded in electoral arithmetic and the perils, as he sees it, of ignoring them. In an age of increasing political polarisation, his voice represents a particular form of anti-tribal tribalism—a cohort united by a belief in pragmatic centrism and a frustration with ideological purity tests.

As one senior broadcast producer noted, “Love him or loathe him, you book Dan Hodges because he never delivers a boring, predictable take. He forces the debate to a different level, often exactly where it’s most uncomfortable for the guests sitting beside him. That’s his value.” This ability to shift and sharpen discourse is perhaps his most enduring contribution. Whether analysing the next Labour leadership contest, the future of the Conservative Party, or the realignment of British politics after Brexit, the insights of Dan Hodges will remain a critical, provocative reference point.

Conclusion

Dan Hodges is more than just a columnist; he is a phenomenon in British political media. From his deep roots in the Labour movement to his current status as its most prominent internal exile, his career trajectory is a compelling sub-plot in the story of the modern British left. His methodology—a blend of contrarian instinct and ruthless electoral realism—provides a distinct and valuable lens on the political game, even when his conclusions provoke anger or disbelief. He embodies the complex, often painful, tensions between principle and power that define democratic politics. To engage with his work is to engage with some of the most critical and contentious questions facing British democracy: Who are political parties for? How do they win? And what compromises are necessary, or unacceptable, on the path to power? In continually asking these questions, Dan Hodges ensures his role remains central to the national conversation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who is Dan Hodges and why is he significant?

Dan Hodges is a prominent British political commentator, columnist for The Mail on Sunday, and author. He is significant for his unique perspective as a former Labour insider who became one of the party’s most vocal critics from the centre-ground, offering strategic analysis focused intensely on electoral practicality and political realism.

What are the core political beliefs of Dan Hodges?

Dan Hodges believes in a form of muscular, electoral-focused centrism. He prioritises national security, a strong Atlanticist foreign policy, and a politics that connects with traditional working-class voters on issues like crime and patriotism. His core belief is that political power, achieved through winning elections, is the essential foundation for any meaningful social democratic change.

Why did Dan Hodges become so critical of the Labour Party?

Hodges became increasingly critical of the Labour Party as he perceived it to be moving away from the electorally successful centre-ground politics of the Blair era, particularly under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn. He argued the party was being captured by a metropolitan activist culture that abandoned its traditional base, making it unfit to win national power.

Which newspapers does Dan Hodges write for?

Dan Hodges is primarily known for his weekly column in The Mail on Sunday. He has also been a regular contributor to The Daily Telegraph and The Guardian in the past. His choice of platform, often right-leaning titles, reflects his political evolution and target audience of disaffected centrists.

How would you describe Dan Hodges’s commentary style?

The commentary style of Dan Hodges is direct, pugnacious, and clear. He employs a contrarian approach to challenge media consensus and focuses relentlessly on strategy and electability. His tone can be scornful of what he views as political dogma, and he is known for his forensic dismantling of arguments he considers unrealistic or detached from public sentiment.